Dr. Baolin Wu, American Academy of Chinese Medicine

Brent Christopher Wulf, American Yijing·Neijing Academy

Time is life itself, and in the ancient Chinese worldview, the five elements begin with wood. This aligns with the

natural cycle of the seasons, where wood represents spring, the season of emergence and the sprouting of new growth. Naturally, one might expect wood to stand at the beginning of every major cycle. Yet in traditional Chinese medicine, a mystery arises within the body’s meridian system. The lung meridian, associated with the

metal element, comes first. The liver meridian, associated with wood, comes last.

Why does the meridian circuit begin with metal and end with wood, when in the seasonal cycle wood initiates the new year with spring, and metal marks the harvest of autumn near the year’s end? Why are the lungs, rather than the liver, given the role of opening the body’s meridian flow?

This apparent contradiction reveals deeper structures hidden within Chinese medicine and cosmology. To resolve it, we must examine the interplay of yin and yang and the five elements across the daily meridian clock, the seasonal calendar, and the natural rhythms of life itself. This article explores why the lung and liver form the two poles that encompass the entire twelve-meridian system, and how understanding their relationship reveals the hidden order of the natural world.

To begin, we will briefly review the twelve meridians and their correspondences. In Chinese medicine and cosmology, the theory of correspondences forms the foundation for understanding the relationships between the body and the cosmos. The following table is provided both as a reference for those already familiar with traditional Chinese medicine and as a helpful guide for readers new to the subject:

In the human body, the lung marks the beginning of the twelve-meridian circuit, while the liver marks its conclusion. The lung meridian belongs to the metal element, and the liver meridian to the wood element. Metal’s movement is inward and downward, characterized by gathering, condensing, and going within, so it suggests harvest, contraction, and consolidation. Wood’s movement, by contrast, is upward and outward, characterized by sprouting and expansion, so it suggests emergence, growth, and extension.

Although metal corresponds to autumn and wood to spring, it may seem puzzling that the lung meridian opens the daily meridian circuit while the liver meridian concludes it. This arrangement, however, can be understood through two key principles: first, the east-west pairing in Chinese thought used to express totality; and second, the twenty-four-hour organ clock in Chinese medicine. In the daily cycle, wood governs the hours from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m., followed by metal, which governs from 3 a.m. to 7 a.m. Each four-hour period is subdivided into two phases, reflecting yin and yang within each element. During wood’s governance, the hours from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. correspond to yang-wood and are associated with the gallbladder meridian,

while 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. correspond to yin-wood and the liver meridian. Under metal’s governance, the hours from 3 a.m. to 5 a.m. represent yin-metal, linked to the lung meridian, and 5 a.m. to 7 a.m. represent yang-metal, linked to the large intestine meridian.

Among the twelve meridians, the lung marks the beginning and the liver marks the end. These two serve as the structural poles (endpoints), encompassing the entire twelve-meridian circuit. A central principle of the Yijing 《易经》 is that every issue can be approached from two sides. Any question or situation always has two poles.

Therefore, to truly understand something, one must first grasp the two endpoints; only then can one comprehend the whole. Even within the “middle,” the law of polarity persists. The ten meridians that reside between the liver and lung form into pairs, consisting of internal-external (表里 biaoli) relationships with one another.

If once focuses on that which is found in the middle, they will not comprehend the whole. Learning should begin by firmly recognizing the endpoints, and only afterward observing how all that lies between arranges itself as reflections of yin and yang. To fall back into thinking through an undefined “middle” is to lose sight of the natural structure established by the endpoints.

The concepts of yin and yang are fundamental to understanding the twenty-four-hour meridian cycle. Each day is traditionally divided into two halves by noon and midnight. Noon marks the sun’s highest point in the sky, while midnight represents its exact opposite. These divisions reflect the dynamic balance of yin and yang, with daylight corresponding to the light and warmth of yang, and nighttime to the darkness and cold of yin. As the day progresses from light to dark and back again, yin and yang do not simply alternate, they transform into one another in a continuous cycle.

Midnight, when yin has reached its fullest, marks the moment when the seed of yang is conceived. This explains why the yang aspect of the wood element, associated with the gallbladder meridian, governs the hours from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. The following hours, from 1 a.m. to 3 a.m., correspond to yin-wood and the liver meridian. Traditionally, around 2 a.m., the first sounds of birds chirping are heard. From 3 a.m. to 5 a.m., yin-metal governs the cycle, corresponding to the lung meridian. In ancient Chinese timekeeping, this was known as the “fifth night-watch” (五更 wu geng), the moment when the rooster’s crow signaled the approaching dawn. Finally, from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m., yang-metal governs, associated with the large intestine meridian, during which the sun begins to visibly rise, birthing the active yang of day.

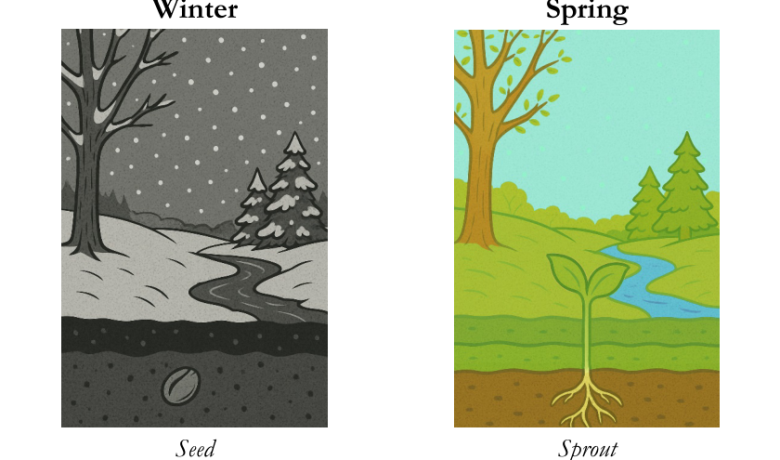

The same pattern repeats on the larger scale of the annual cycle. In the traditional Chinese calendar, the year is divided into twelve lunar months, each corresponding to one of the twelve Earthly Branches. The eleventh month, whose midpoint contains the Winter Solstice, is assigned to the Earthly Branch Zi (子). A Chinese character that also means ‘seed’ and is numerically listed as the first in the standard sequence of the twelve

Earthly Branches. Given its connection to midnight, during the hours from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., one might expect it to mark either the first month or the final twelfth month of the year. However, the Zi (子) month is designated as the eleventh month.

This was not always the case. During the Zhou era, the calendar year began with the Zi- month (子月), which is centered around the winter solstice, marking the start of the year in the heart of winter. However, in 104 BCE, Emperor Wudi’s Taichu reform introduced significant changes to this system. This reform adopted the Xia-style calendar, which formally incorporated the 24 solar terms (节气jieqi), dividing the solar year into 24 segments based on the sun’s position along the ecliptic. The first solar term, “Beginning of Spring” (立春 Lichun), was designated as the start of the new year. This in effect, reassigned the first month of the year from the mid-winter Zi-month to the Yin-month (寅月). This adjustment effectively moved the beginning of the year from the middle of winter to early spring.

This stands in contrast to the Western calendar, where January 1st marks the beginning of the year not because of astronomical necessity, but as a result of Roman political reform. Instituted by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, this date aligned with administrative cycles rather than natural phenomena. The month was named after Janus, the Roman god of transitions, and chosen for its symbolic value rather than any astronomical observation. This reform moved away from earlier Roman calendars, which were lunar or lunisolar in nature. Today, the Gregorian calendar months are not aligned with the moon’s cycles or the sun’s position in the zodiac or any constellations.

To keep the calendar aligned with the solar year, the Julian calendar, and later the Gregorian reform, established a fixed year length of 365 days, with a leap year added approximately every four years to account for the actual solar cycle of about 365.25 days. This adjustment helps maintain general alignment with the seasons. However, the division of months and the designation of January 1st as the beginning of the year were based on political decisions made in ancient Rome, not on any observable natural cycle. Though this system has endured for centuries, it reflects the legacy of an empire long gone, rather than a measured coordination with seasonal or astronomical phenomena.

Although the Winter Solstice, which occurs around December 21st or 22nd, marks the return of the sun and the gradual lengthening of daylight, January 1st holds no direct astronomical significance. It falls roughly eleven days after the solstice and just a few days before Earth’s perihelion, its closest point to the sun, which usually occurs between January 3rd and 5th. While these events are scientifically notable, they were not

the reasons behind the selection of January 1st as the start of the new year. In the end, the placement of New Year’s Day in the western calendar is no more grounded in natural cycles than the time clocks we follow today.

Before the invention of mechanical clocks, time was measured directly by the sun. Solar noon, the moment when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, was a natural reference for midday, though its exact timing varied slightly by location and season. Ancient civilizations used instruments like sundials, gnomons, and shadow sticks to track this moment with remarkable accuracy. However, the synchronization between human timekeeping and the natural cycles of the sun gradually drifted apart.

Modern clock time, standardized through mean solar time and later regulated by atomic clocks, is no longer based on the sun’s actual position. This disconnect widened in the 19th century with the adoption of time zones and global synchronization, and is further compounded by policies like daylight-saving time, which artificially shift the hour forward or backward, adding yet another layer of separation from the natural rhythms of the Earth.

Unlike the Roman-based calendar, the traditional Chinese calendar is rooted in systematic astronomical observation. It follows a lunisolar structure, coordinating the moon’s phases with the sun’s position along the ecliptic. Central to this system are the twenty-four solar terms (节气jieqi), which divide the solar year into twenty-four equal parts based on the sun’s celestial longitude. As the Earth orbits the sun, it moves

approximately 15 degrees along the ecliptic every fifteen days. Each solar term corresponds to one of these 15-degree intervals and marks observable seasonal transitions such as warming weather, increased rainfall, plant sprouting, or animal migrations.

The Chinese New Year is intentionally placed near Lichun (立春), the “Beginning of Spring,” the solar term that begins when the sun reaches 315 degrees of celestial longitude. This placement is not based on symbolic preference but reflects a precise synchronization of the solar and lunar calendars. Since the lunar cycle is

approximately 29.5 days, twelve lunar months produce a year that is about 11 days shorter than the solar year. To correct this gap, an intercalary or leap month is inserted roughly every two to three years in order to keep the lunar months aligned with the solar terms and seasonal patterns.

As a result, Chinese New Year does not fall on a fixed solar date but is calculated as the second new moon after the Winter Solstice. This ensures that it always occurs between mid-January and mid-February, close to the seasonal shift marked by Lichun. Supplemented by cosmological frameworks such as yin-yang theory and the five elements (五行 wuxing), the Chinese calendar integrates timekeeping with the body, nature, and the cosmos as a unified whole.

This passage has traditionally been interpreted to mean that during deep rest, blood circulating through the limbs and surface of the body withdraws inward and is stored in the liver’s network of vessels, known as hepatic sinusoids. As a result, the hours from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m., which correspond to the Gallbladder and liver meridians, are considered the most vital time for the liver to gather, nourish, and restore the blood. This replenished blood then supports the sinews and helps maintain clear vision in the waking hours that follow.

During deep sleep, typically between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m., the liver plays a critical role in detoxifying the blood, processing metabolic waste, and recycling red blood cells. This period also supports glycogen storage, providing a reserve of glucose for energy needs upon waking. Additionally, blood flow is redirected from the muscles and peripheral tissues toward the inner organs during deep sleep, concentrating in the liver to support regeneration and immune function. This redistribution of blood might be seen as a form of “storage,” where the liver gathers and refreshes the blood for daytime use, aligning with the classical idea that the liver stores and nourishes blood during the stillness of night, preparing the body for the active yang phase of the day.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, the transformation times of yin and yang are used in maintaining balance and longevity. This occurs at midnight and noon, when one phase reaches its peak and gives rise to the other. These moments are considered energetically pivotal, when the body should ideally enter a state of sleep in order to harmonize with the transformation. This is also why true solar noon and true midnight are considered especially important. Solar noon marks the peak of yang, when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky. True midnight marks the depth of yin, when yang is first conceived in the stillness of the night.

Laozi, Sun Simiao, and Ma Danyang often emphasized the importance of resting at noon, specifically between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. Even if only for a short nap, to align the body with the midday transition. This practice is known as the Midnight-Noon Zi-Wu nap (子午觉), referring to the two pivotal yinyang hours of the twenty-four-hour cycle.

Likewise, sleeping between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m., during the Zi-hour (子时), is considered essential. As this is the time when yin reaches its deepest point and the seed of yang is conceived within it. A short rest between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m., as the sun rises and yang begins to strengthen, is also recommended. In Daoist traditions of

health and longevity, the proper timing of sleep, along with the careful regulation of diet, exercise, and emotions, forms the foundation for aligning the body with the larger rhythms of nature and the cycles of the cosmos.

The impulse to move arises only after one has truly rested. This is yin giving rise to yang, just as winter gives birth to spring. In the context of physical exercise, strenuous movement causes microscopic tears in the muscle fibers. But growth does not happen during the workout. It occurs afterward, particularly during sleep, when the body enters a state of restoration. During this yin phase, the process known as muscle protein synthesis repairs and strengthens the damaged tissue, forming larger and more resilient muscles.

This is yin responding to the completion of yang. After intense exertion, the body naturally seeks rest. Some people even fall asleep immediately. Yet it is not the exercise itself that makes the muscle grow, it is the sleep that night that regenerates and rebuilds the body. This principle is well known among bodybuilders, who often observe that they appear physically larger and fuller after rest. The visible result is yang, but the transformation is made possible by yin.

Just as a mother conceives a child through union with the father, yet we do not mark the beginning of the child’s life at conception, but rather at birth. Though we know life truly begins at the moment of conception, its growth is invisible, unfolding silently in darkness. This reflects a universal rhythm: the seed of life takes form in the silent darkness, long before it is seen.

In the same way, the seed of the year is conceived at the winter solstice, deep within the season governed by the water element. In this dormant phase, surrounded by stillness and cold, the seed quietly gestates. The calendar marks the beginning of the year only when that seed breaks ground in spring, when growth becomes visible. Similarly, your birthday is celebrated on the day you were born, when you emerged out into the world, not the day you were first conceived.

During the lunar Zi-month (子月), the seed of yang remains still, surrounded by the freezing waters of winter. Botanically, this phase corresponds to imbibition, the stage when a seed absorbs moisture and begins to swell, initiating the first subtle movements of life. This is analogous to the moment of conception. In the following

lunar Chou-month (丑月), the seed anchors itself: the radicle (root tip) breaks through the seed coat, grows downward, and begins nutrient absorption. Finally, in the lunar Yin-month (寅月), the shoot forms and pushes upward, breaking through the soil surface to emerge as a sprouting stem. This sequence mirrors the daily cycle: just as yang is conceived at midnight and rises visibly at dawn, so too does the plant’s visible growth begin after hidden germination. Photosynthesis begins, and the plant initiates its upward and outward journey, following the path of yang.

Without water, wood cannot germinate; without the seed, water cannot bring life into being. In the five elements generating (生) sequence, water gives birth to wood (水生木). The seed (子) of yang is conceived within water, yet it does not emerge immediately. It must first pass through the lunar Chou-month (丑月). Only after this incubation does it begin to emerge with the lunar Yin-month (寅月), which is marked with the solar term Lichun (立春), the “Beginning of Spring.”

This same sequence is mirrored in the traditional Chinese division of the day into twelve double-hour periods. The seed of yang is conceived during the most yin time of the day, midnight, in the Zi-hour (子时) from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., governed by the Gallbladder meridian, associated with yang-wood. Yet emergence does not occur all at once. From there, yang continues its hidden development through the Chou-hour (丑时) from 1 to 3 a.m., associated with the Liver meridian and yin-wood. Only after this incubation does it begin to emerge with the Yin-hour (寅时) from 3 to 5 a.m., associated with the Lung meridian and yin-metal, which is marked by the rooster’scrow announcing the emergence of yang.

While life begins at the moment of conception, we celebrate the day of birth when a child emerges into the world. In the same way, although the new year is conceived at the winter solstice, it is not acknowledged until it visibly arises at the “Beginning of Spring” (立春 Lichun). This marks the moment when vegetation breaks through the soil, life reawakens from its dormancy, and the natural world enters a period of renewal. Just as sunrise, rather than midnight, is commonly regarded as the true beginning of the day, the visible emergence of life in spring is seen as the true start of the year. This perspective reflects the fundamental distinction between the hidden, gestational nature of yin and the manifest, active quality of yang.

The seed of life forms in an earlier, concealed phase, developing within the stillness of winter. Whether within the mother’s womb or within the waters of the five elements, this hidden stage belongs to the yin realm of formation. Midnight, the winter solstice, the Zi-month (子月), and the Zi-hour (子时) all symbolize this period of inception. In Daoist thought, yin is regarded as the source of yang, just as mothers give birth to children. Life arises from stillness, and movement is born from rest. The emergence of yang is not the moment of origin but the moment when the unseen becomes visible, when the seed breaks through the surface to become a sprout. This is the foundational principle that yang arises from yin, making visible the growth that had quietly formed

in the depths of winter.

In ancient China, this pattern was recorded in the Book of Han (汉书):

A similar principle can be observed in how cultures structure the week. Some recognize Sunday as the first day, while others consider Monday the true beginning. In his teachings, Master Du mapped the eight trigrams (八卦 bagua) onto the seven days of the week, integrating the five elements (五行) into this sequence. Monday was associated with the Qian (乾) trigram, which he linked to the wood element. The generative sequence of the five elements then proceeded through the days, concluding on Friday with the Xun (巽) trigram, representing the water element. Saturday continued this water phase with the Kan (坎) trigram.

Sunday is associated with two trigrams: Gen (艮) and Kun (坤). Gen, the immovable mountain, symbolizes the stopping point of the week, a time for rest and introspection. It is paired with Kun, the most yin of the eight trigrams, representing the nurturing, receptive qualities of Earth. In this way, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday together form the yin phase of the weekly cycle, generating the renewal of yang with Monday, when the

week begins again. This structure mirrors the larger cycles of birth, growth, and rest, reflecting the natural rhythms of yin and yang.

In many cultures, Sunday naturally evolved into a day of rest and recovery, a time of fasting or quietude for at least part of the day. Monday, in contrast, is widely recognized as the start of the active workweek, when people transition from inward rest to outward engagement. In this light, Monday parallels the emergence of yang: a movement outward into activity, rising from the repose of Sunday.

The conception of the seed begins at the Winter Solstice, corresponding to midnight within the daily cycle. This phase can be likened to the conception of a child within the watery womb of the mother. Just as the seed lies dormant through winter before sprouting in spring, the child gestates unseen before being born into the world. The rising sun at dawn mirrors the emergence of life from hidden gestation.

Just as the rooster crows, signaling the first light of day and the activation of the lung meridian, plants also respond to the approach of dawn. They possess internal circadian clocks that anticipate daily light cycles, priming their photosynthetic processing in advance. This preparation allows them to capture the first rays of the sun and begin producing oxygen as soon as light levels cross the compensation point. Just as a child’s first breath marks the moment of independent life, the first burst of oxygen from a plant signals its emergence into the broader cycle of life and interaction with the world.

The Lungs initiate the first breath of life, marking the true beginning of individual existence. In traditional Chinese obstetrics, the moment a newborn emits its first cry is known as “seizing the qi of life” (夺胎之气 duo tai zhi qi). Through this initial breath, the infant transitions from gestating to living. Thus, the lungs are regarded as the organ connected to the birthing of yang life into the world. This process mirrors the daily rhythm, where the hours governed by the Metal element (3 a.m.–7 a.m.) mark the dawn. Just as plants begin to release oxygen as the first light of dawn initiates a new day, the newborn takes its first breath upon entering the world, marking its own emergence into life.

This meridian sequence, where wood comes before metal, reflects the classical aphorism in Chinese medicine: “Blood mothers Qi” (血为气母). In this context, blood is primarily associated with the liver, which governs the hours from 1 a.m. to 3 a.m., while qi is associated with the lungs, which govern the hours from 3 a.m. to 5

a.m. After the liver gathers and refreshes the blood during the stillness of night, it sets the stage for the lungs to initiate their wakeful breath, ushering in the activities of the new day.

This generative sequence from wood to metal can also be seen in the sun’s path across the sky. In traditional Chinese thought, wood is associated with the east, where the sun rises, and metal with the west, where it sets. According to classical cosmology, the sun is said to rise from the eastern ocean and set behind the Kunlun Mountains in the west, symbolizing the full arc of life from birth to completion. This reflects the same principle discussed earlier, where the seed of yang, having been born from the deep, watery stillness of night, rises into the active phase of day, only to return to rest as the sun descends in the west. Just as the sun completes its daily journey, the week concludes with the Gen (艮) trigram, which represents the stillness of a mountain,

marking a return to the source.

Chinese often signals totality by pairing two extremes, a rhetorical device called 对举(duiju). When the poles “east” (东 dong) and “west” (西 xi) are written together as “east-west” (东西), the compound can reach beyond its literal axis. For example, in movement phrases such as 他在城里东西乱跑 (“He ran east-west across the city”) the reader understands crisscross travel that covers every quarter (north, east, west, south), not just the eastern and western streets. In distribution or coverage statements like 这条铁路贯穿东西 (“The railway spans east and west”) the sense expands to the full breadth of the land. Even as a noun meaning “thing, stuff,” 东西 functions as an unlimited container: 市场上什么东西都买得到 implies that every imaginable item is

for sale. Writers can exploit this meristic power to hint at completeness without listing each element. In this way, the lung meridian and liver meridian can be seen to encompass all the meridians.

In Chinese, the concept of totality is often conveyed through merism (对举 duiju), a rhetorical device that expresses a comprehensive whole by pairing two contrasting or complementary elements. For instance, the directional poles “east” (东 dong) and “west” (西 xi) are commonly combined to form the phrase “east-west” (东西 dongxi), which extends beyond its explicit directional axis. In phrases like “He ran east and

west across the city” (他在城里东西乱跑 ta zai cheng li dong xi luan pao), the meaning shifts from a literal path to a broader sense of movement in every direction, including north and south. Similarly, in statements like “This railway spans east and west” (这条铁路贯穿东西 zhe tiao tielu guanchuan dong xi), the phrase takes on a sense of complete coverage, suggesting a thorough connection across the landscape.

Even as a noun, 东西 (dongxi) is used to mean “things,” capturing the idea of an unlimited, all-encompassing range of objects. For example, the statement “At the market, you can buy anything” (市场上什么东西都买得到 shichang shang shenme dong xi dou mai de dao) implies that every imaginable item is available, emphasizing the full spectrum of possibilities. This rhetorical device, merism (对举 duiju), is used to evoke completeness without enumerating every part. In the same way, the Lung and Liver meridians, positioned as the first and last in the twelve-meridian sequence, encompass the totality of the meridian system.

In understanding the meridian system, we see that the apparent contradiction between the lung and liver as the first and last meridians is not a flaw, but a reflection of a deeper order. Just as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, the lungs and liver frame the human body’s meridian circuit, encompassing the full arc of life from the first breath to the final pulse of blood. This perspective reveals that what seems like an inconsistency is actually a profound expression of natural law, where the visible and the hidden, the manifest and the latent, are woven together in a seamless flow.

Ultimately, this study of the meridian system is not merely a technical inquiry, but has been a path to understanding how life itself unfolds. It reminds us that each cycle, whether of a single day or a full lifetime, is part of a greater whole. Just as the seed must lie dormant before sprouting and the sun must set before it rises again, each moment contains the promise of renewal. In this way, the lung and liver stand not just as the beginning and end of a circuit, but as gateways to a deeper understanding of the cycles of existence.

When you do something, others may not believe you have begun until they see you take visible action. Only once they observe your movements do they say you have started. Yet in truth, every action does not originate with the movement of the body, but with the conception of intention from within. What people see is the outward expression; what truly initiates the action lies hidden within.

No one sees your willpower, but they can see your actions. This is why people often measure one’s willpower by what they have accomplished in life. In Daoism, merit is not granted for merely having the intention to do good, but for the actual performance of good deeds. It is the realization of intention through action that brings value and meaning. This mirrors the principle of conception and birth: we celebrate the day you were born with recognizing your birthday, not the day you were conceived. In the same way, the merit of a life is measured not by thoughts of doing good, but by the good deeds actually brought into the world.

The virtue of spring is expressed in the active renewal of life after the stillness of winter. The birth of children is a virtue, as is the rising of the sun at the start of a new day. Virtue reveals itself in actions that nurture and renew life. It is expressed in actions that foster growth and sustains life.

微信扫一扫打赏

微信扫一扫打赏